Dr. Robert Geller shakes up assumptions about earthquake prediction

For over 40 years, the Japanese government has issued seismic hazard maps that indicate which parts of the country are most in danger of a serious earthquake. Currently, the area of greatest interest to forecasters is the Nankai Trough region, a fault zone off the east coast of Japan running along the shores of Shikoku and up to Wakayama Prefecture. According to official forecasts, there is an 80% chance that a major earthquake will strike the region within the next 30 years, a probability that has shaped disaster response considerations.

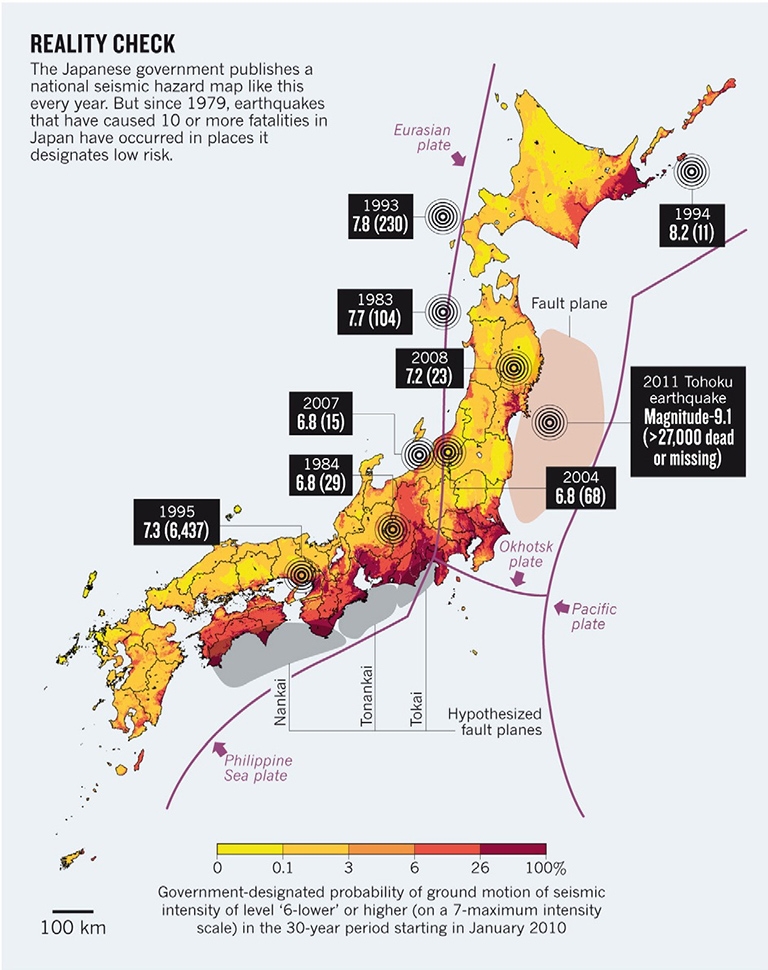

Some researchers, however, have been critical of the government’s forecast methods. Dr. Robert Geller, professor emeritus of the University of Tokyo in the field of seismology, has published numerous works laying out his position that neither short-term predictions nor long-term forecasts are feasible. In fact, he argues, such predictions may end up being harmful if regions forecasted to have a low earthquake risk are lulled into a false sense of security.

Speaking at the Foreign Correspondents’ Club of Japan, Dr. Robert Geller bluntly titles his talk “The ‘Imminent’ Nankai Trough Mega Quake: Myth or Reality?” His opening is equally blunt: “It’s a myth.”

The Japanese government’s hazard maps go back to the 1970’s, when a scientific report announced a high likelihood of a powerful earthquake striking the Tokai region between Nagoya and Tokyo. In response, the government passed the Large-Scale Earthquake Countermeasures Act in 1978, which mandated regular forecasts of impending earthquakes. In the four decades since, no major earthquake has struck the Tokai region.

Dr. Geller’s contention is that this law was passed before the Tokai quake prediction could be tested and verified, and that subsequent events and research have cast strong doubts on the usefulness of forecasts. “Short-term prediction of imminent earthquakes is impossible, because they are what’s known in physics as a chaos-type process: any small variation in the parameters completely screw up your ability to predict what’s going on,” Dr. Geller explains. “And long-term prediction is impossible because quakes don’t repeat in cycles, there is no statistically significant evidence for cycles.