OTHER

Considering the Benefit of Inconvenience

People totally immersed in convenience grow weak

March 15, 2018

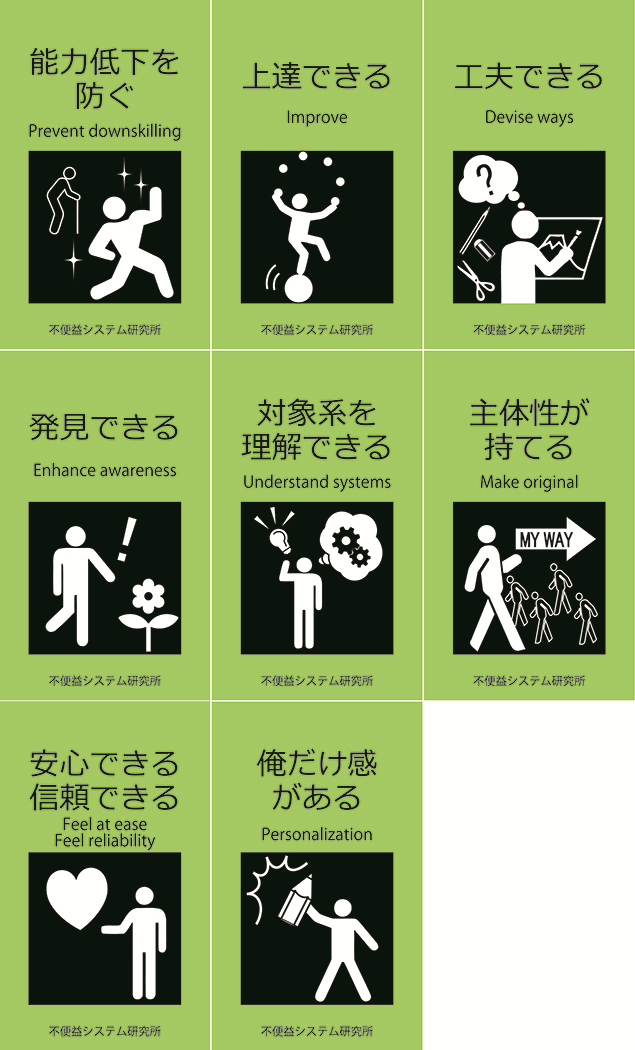

People have long loathed inconvenience. But isn’t it possible that a certain kind of joy can be obtained from inconvenience itself, from the fact that something requires a little extra effort? What do humans have to offer as a result of their pursuit of efficiency? This conversation between Hiroshi Kawakami and Toshihiro Hiraoka, researchers in the “benefit of inconvenience,” or Fuben-Eki, attempts to reaffirm the appeal behind the benefits surrounding inconvenience.

Left : Toshihiro Hiraoka

Assistant Professor, Department of System Science, Graduate School of Informatics, Kyoto University

Born 1970. Completed a master’s degree in precision engineering at Kyoto University Graduate School of Engineering, then worked for Matsushita Electric Industries (now Panasonic) before assuming his current position. Specializes in human-machine systems, with research focusing particularly on driver assistance systems. Holds a Ph.D. in Information Science.

Right : Hiroshi Kawakami

Professor, Unit of Design, Kyoto University

Born 1964. After completing a master’s degree in precision engineering at Kyoto University’s Graduate School of Engineering, went on to work as an associate professor at Okayama University, then an assistant professor at Kyoto University before assuming his current position. Research focuses on system design theory. Holds a Ph.D. in Engineering.

Assistant Professor, Department of System Science, Graduate School of Informatics, Kyoto University

Born 1970. Completed a master’s degree in precision engineering at Kyoto University Graduate School of Engineering, then worked for Matsushita Electric Industries (now Panasonic) before assuming his current position. Specializes in human-machine systems, with research focusing particularly on driver assistance systems. Holds a Ph.D. in Information Science.

Right : Hiroshi Kawakami

Professor, Unit of Design, Kyoto University

Born 1964. After completing a master’s degree in precision engineering at Kyoto University’s Graduate School of Engineering, went on to work as an associate professor at Okayama University, then an assistant professor at Kyoto University before assuming his current position. Research focuses on system design theory. Holds a Ph.D. in Engineering.

Hiraoka: Professor Kawakami, your specialty is artificial intelligence, isn’t it? How did that lead you to explore the subject of inconvenience?

Kawakami: It all began when I first started as a (then) assistant professor at Kyoto University, and Professor Katai, who ran the lab at the time, told me that the benefit of inconvenience, or what we call Fuben-Eki, was a subject whose time was coming. H: So you gave up artificial intelligence?

K: No, no. I haven’t exactly given it up, but the benefit of inconvenience just seems so much more interesting than trying to replicate human intelligence with machines, don’t you think? H: When I was a student, I also did research in artificial intelligence under Professor Katai, so I kind of had a sense of the benefit of inconvenience even before there was a term for it. Later, though, I moved on to studying controls.

K: When you first came back to the university after having worked at a company, weren’t you studying controls for automated driving systems for cars? H: That’s right.

K: How did you end up shifting to your current field of research?

H: I gradually moved from studying automated driving to researching driver assistance systems. I guess for a car enthusiast like me, a car that drives itself just isn’t a real car! (Laughs) As I pursued that research, I thought it would be a waste if all the system did was send out information. At the same time, I also wondered if, with a little creativity, we could get the system to send out the right information that would allow drivers to drive better by thinking for themselves and putting in a little effort.

K: That’s exactly what we mean by Fuben-Eki.

H: I think there must be some way to use driver assistance systems to encourage drivers to feel that driving safely or more ecologically can be fun. To do that, we need some kind of hook to get them to try the system, and then a way to keep them using it without turning drivers off.

K: So the important thing is to get the driver to feel some attachment to the system, even if it’s a little more trouble to use.

Kawakami: It all began when I first started as a (then) assistant professor at Kyoto University, and Professor Katai, who ran the lab at the time, told me that the benefit of inconvenience, or what we call Fuben-Eki, was a subject whose time was coming. H: So you gave up artificial intelligence?

K: No, no. I haven’t exactly given it up, but the benefit of inconvenience just seems so much more interesting than trying to replicate human intelligence with machines, don’t you think? H: When I was a student, I also did research in artificial intelligence under Professor Katai, so I kind of had a sense of the benefit of inconvenience even before there was a term for it. Later, though, I moved on to studying controls.

K: When you first came back to the university after having worked at a company, weren’t you studying controls for automated driving systems for cars? H: That’s right.

K: How did you end up shifting to your current field of research?

H: I gradually moved from studying automated driving to researching driver assistance systems. I guess for a car enthusiast like me, a car that drives itself just isn’t a real car! (Laughs) As I pursued that research, I thought it would be a waste if all the system did was send out information. At the same time, I also wondered if, with a little creativity, we could get the system to send out the right information that would allow drivers to drive better by thinking for themselves and putting in a little effort.

K: That’s exactly what we mean by Fuben-Eki.

H: I think there must be some way to use driver assistance systems to encourage drivers to feel that driving safely or more ecologically can be fun. To do that, we need some kind of hook to get them to try the system, and then a way to keep them using it without turning drivers off.

K: So the important thing is to get the driver to feel some attachment to the system, even if it’s a little more trouble to use.