OJIYACHIJIMI

Member of the Japan Professional Photographers Society. She has been covering manual labor and craftwork in her travels around Japan and overseas for 25 years. Her lifework has been to photograph indigenous natural surroundings and the culture connected to it in the islands of Oceania and the Pacific Rim, Asia and Europe. She is the author of Fiji no Maho (The Magic of Fiji) (Chihaya-shobo), and has held numerous exhibitions.

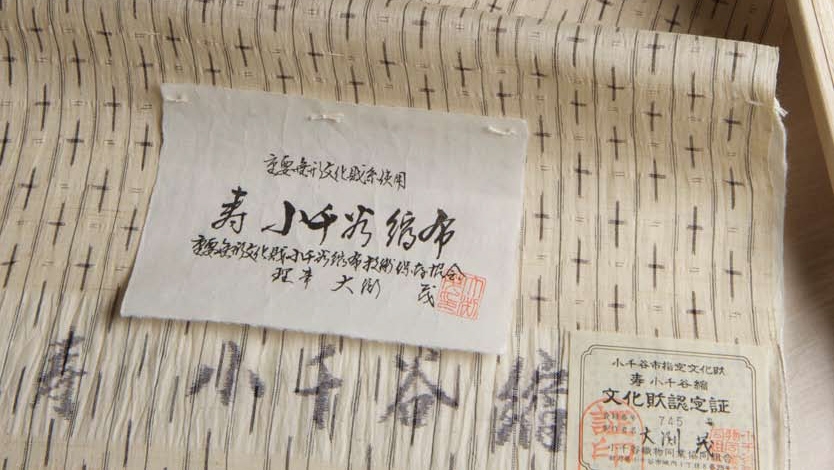

Plant fibers spun one by one into twists of thread are woven into cloth. It has been called“ Nature’s cloth”— a fabric that has been made for thousands of years with astounding effort. Ojiya-chijimi is a textile with a history, and it requires a unique process of snow-bleaching as part of its production. Tough yet soft on the skin, this textile also exudes a refined artistic beauty.

Ojiya is located in a rich grain-producing region through which the Shinano River meanders, providing the surrounding area with water. These fertile lands also become fields of snow for five months in winter.

It was after several days of snowstorms that spring finally arrived, and the contrast between the blue sky and snow fields bathed in spring sunshine was especially dazzling. Rows of light-colored kimono cloth—finished woven cloth made from thread with three months of painstaking effort —were laid out rainbow-like on the snow, almost like some modern art installation.

The final stage in producing Echigo-jofu and Ojiya-chijimi textiles requires exposing them to snow, a process which makes use of the bleaching effect from ozone produced when snow evaporates in the sun. The wisdom of ancestors has been passed on through this method that removes excess dye, loosens snarls in the threads, and gives the cloth a light, soft finishing touch.

“Yarn is formed in snow, woven in snow, rinsed in snow-water, and bleached in snow. There’s cloth because there’s snow…. You could say snow is the parent of this cloth.”

This is a line from Hokuetsu Seppu (Snow Stories of North Etsu Province), written in the Edo period by Bokushi Suzuki, a man of letters from Shiozawa. He went to investigate Echigo province and the people of the snow country personally in order to write and illustrate the book. That passage was also used by Nobel prize-winning author Yasunari Kawabata in his novel Snow Country, to create layers of imagery depicting the cleanliness which the main character—a man from Tokyo—finds so attractive in the lover from Echigo whom he has travelled to meet.

The people of Echigo certainly do have a disposition that is snow-like in its purity, along with a tenacity acquired from having to live with heavy snow. No one could survive by themselves in such an environment, and the people have a deeply-rooted spirit of mutual support.

Long Months Spinning Fiber Into Yarn

Early morning and it is still dark. The paper-screen covered window is white with a cozy brightness generated by the snow. Grandma quietly gets up so as not to disturb the grandchildren, and goes to the living room where she inserts feet into the kotatsu (heated table) to warm up, and gets on with work. With total concentration she sets about spinning the yarn with her hands, plying them the same as she did yesterday, and the day before that.

Delicate fibers of karamushi, also known as choma, the plant used to make the ramie yarn used in Ojiyachijimi, are laid out like a spiders web on the black cloth spread over her knees. Spine straight and eyes narrowed, she focuses her concentration on her fingertips. She takes the threads from a thick telephone directory where they have been carefully pressed and, occasionally putting them into her mouth to apply moisture, fastens them together. She joins another thread to the end, puts it on the loom and forms the thread. The only sound in the room is the ticking of the clock. All is quiet in the faint light of dawn. Snow absorbs the noise of the world, and only the sound of silence rings through the bracing air.

“Karamushi breaks easily when there’s no humidity,” she murmurs as her long-practiced hands fasten the threads.

“In the past four of us women used to sit round the kotatsu together and work, but we kept quiet and concentrated.”

(laughs)

It felt good to concentrate like that she explained. Her face looked dignified, filled with a Zen-like presence. If there weren’t such ties between people, Echigo cloth would not exist.

When winter comes the women gather inside, moving their fingers in silence. With great care they spin the ramie yarn as it grows by millimeters and centimeters. The painstaking work continues in silence, with the great patience required by such manual labor, until in early spring the woven kimono cloth is laid out on the snow fields in clear weather.