The Aesthetics of the Joiner’s Art The Pride of Japanese Furniture

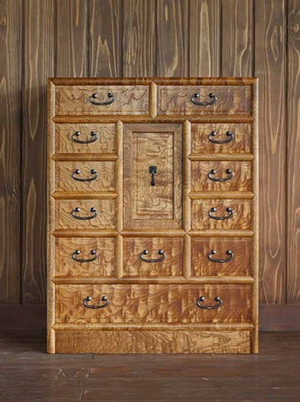

Warmth and solidity, and the burnished glow of wood grain:

Japanese furniture has an exceptional presence,

Even more so when the wood used is so remarkable.

With centuries-old precious woods exceedingly rare today, we visited the workshop of a cabinetmaker who insists on using only natural wood.

Thousands of pieces of precious wood, gathered from throughout Japan.

The rare natural woods lying in this warehouse have all been drying for more than 20 years. Toshio Oyamada examines a slab from an enormous ash felled in Asahikawa. The giant was estimated to have been about 400 years old.

A massive warehouse surrounded by trees at the foot of Mt. Fuji. Opening the door, I’m surrounded on all sides by piles of lumber, some of the pieces taller than myself, closing in like a mountain range. Pieces of fine wood numbering in the thousands, too heavy for one person to carry, lie covered in dust. Seeing me staring at them wordlessly, Toshio Oyamada says, a bit shame-faced, “I guess I got a little carried away.”

The temperatures, seasonal changes, dryness of the air, and other conditions around Mt. Fuji make the region ideal land for storing and working with natural wood. While the area prospered as a center for handmade furniture through about 1955, it eventually bowed to the popularity of steel furniture, and one by one the region’s skilled cabinetmakers disappeared. It was in the late 1980s that Mr. Oyamada decided to revive cabinetmaking here at the northern foot of Mt. Fuji, spending nearly a billion yen to buy up choice wood from around the country, and devoting himself to building furniture. He does more than just make furniture himself; to nurture a new generation of traditional Japanese cabinetmakers, he’ s supervised dozens of young people, and invested his own funds. And yet, not even a handful of them have fully grown into the craft. While cabinetmaking certainly requires dexterity, in fact it is solitary work that also requires a great deal of patience. The only way to become an expert joiner is to repeat the same tasks over and over, building up experience. It’s difficult to expect young people today to have the patience to get that far.

The rare natural woods lying in this warehouse have all been drying for more than 20 years. Toshio Oyamada examines a slab from an enormous ash felled in Asahikawa. The giant was estimated to have been about 400 years old.

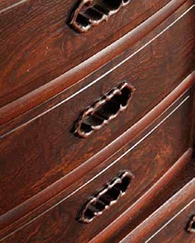

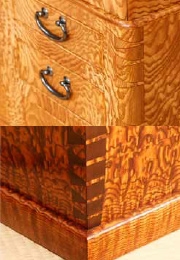

Mr. Oyamada was born in the town of Fujiyoshida in 1938, the sixth of eleven children of parents who owned a gardening business. After graduating from middle school, he served as a live-in apprentice at Ito Woodworking, in the Okuchi section of Yokohama’s Kanagawa Ward, and there he learned the basics of cabinetmaking. Under the master’s supervision, he learned to identify the properties of various woods, how to cut wood within the smallest tolerances and match hand-crafted interior fittings, and even acquired the techniques for creating curved kumiko (mullion work), which require sophisticated design skills. Mr. Oyamada, with his dexterous fingers and his powerful attraction to the beauty of wood, rapidly improved his skills, and eventually struck out on his own while still a young man.