A. The ideal Edo period garden, combining form and function. by Isoya Shinji

During the Edo period, daimyo lords, who were required to split their time between their own domains and the capital city of Edo (Tokyo), competed to construct large gardens at their residences.

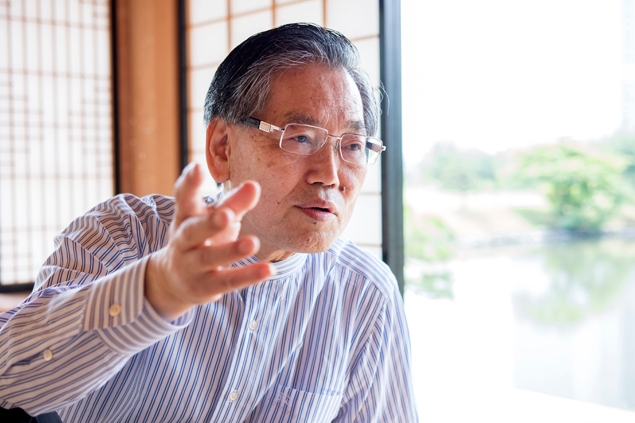

There were once a thousand such gardens, and though they disappeared in quick succession following the Meiji Restoration, even now a handful remain to evoke the atmosphere of the Edo period. Professor Isoya Shinji , a leading expert in landscape architecture, explains the origins and significance of daimyo teien, and the best ways to enjoy these priceless gardens.

A Perfect Balance of Scenery and Practicality Gives Daimyo Teien Their Incredible Allure

Daimyo teien are, as the name suggests, the teien (gardens) of the samurai class. These are totally different to the garden of the priest, or that of the noble, and most definitely more than just superficially charming. Hamarikyu Gardens, for example, were originally the “seaside gardens” (hama no gyoen) of the shogun's coastal residence. Hamarikyu has two duck ponds, known as Shinzeniza and Koshindo, which were used for duck-hunting. There were also areas for horse-riding and archery. A warrior had to be battle-ready at all times, so honing one's martial skills was a routine part of daily life. Therefore the gardens were equipped with facilities of this sort.

Because the owner of Hamarikyu constructed the garden with potential combat in mind, its design and location also serve a strategic purpose. Enclosed by a solid stone wall, with a masugata double gate at the entrance, Hamarikyu has the trappings of a castle. Traveling from Edo Castle along the Yamashita moat and down the Tsukiji River to the boat landing, in an emergency one would have been able to access the open sea. In other words, the garden is designed to facilitate flight if the shogun was trapped.

That said, samurai were not constantly spoiling for a fight. They prepared themselves for both war and peace, with the skills to achieve their aims through diplomatic hospitality as well as battle. Gardens were highly prized as settings for such diplomacy.

Hamarikyu Gardens include the Nakajima-no-Ochaya (Island Teahouse) and Matsu-no-Ochaya (Pine Teahouse) plus the recently restored Tsubame-no-Ochaya (Swallow Teahouse), which were used for socializing and entertaining. Tea, alcohol and food were served, and of course women gathered there as well. The garden was more than just a refined place to appreciate the scenery. It was the setting for political intrigue, and a place to enjoy diverse pleasures, encapsulating the entirety of Edo-period culture.

In Professor Shinji's opinion, viewing Japanese gardens through the lens of Zen or wider Buddhist thought has the opposite effect of making them hard to understand. Any discussion of gardens, he says, must start by acknowledging that first and foremost, they are places to be enjoyed.

Beauty in a Garden Arises from Practicality and Purpose

Crucial to the culture of landscape architecture is the harmony of utility and scenery. By utility we mean practicality, and by scenery, the garden's visual qualities, such as the attractive nature of its vistas. Aiming for a balance between and consideration for these things is fundamental to garden design, and this holds true for all gardens. Beauty can only emerge from the unity of utility and scenery.

When it comes to daimyo teien, utility was not only military. Hamarikyu encompassed medicine, food and agriculture as well, with a medicinal herb garden, vegetable garden, plum trees, tea field, and rice paddies on the grounds. And in the spirit of the later drive toward shokusan kogyo (increasing production, encouraging industry) Hamarikyu became the site for historic sweet potato cultivation trials by scholar and scientist Aoki Konyo. Today we might call it industrial promotion. In those days a statesman's interest in the world had to encompass industry, culture, the arts, education and more. Thus the daimyo teien was a place for putting into practice all the things that underpinned samurai society, an open space with a wide range of roles.

Essentially an Enclosure for a Scaled-Down Ideal

Creating a garden starts with enclosing a space, and in fact the English word garden originally refers to such an enclosure. The space is enclosed using any one of a number of methods, such as a stone wall, fence, or moat. On the largest scale, this could mean having your garden surrounded by mountains. A microcosm in a basin, so to speak. Enclosure is a fundamental requirement for any space in which human beings are going to feel secure. This is why Japan's ancient capitals were all situated in basins.

So we take a space, enclose and secure it, and build our ideal world, our Eden, inside.

What constitutes that ideal has varied over the centuries. In ancient times people kept things simple with the worship of gods and buddhas. In the early modern period, having begun to acquire economic clout and technical ability, people started to build the worlds and landscapes to which they aspired. For example, Koishikawa Korakuen includes famous sightseeing destinations from Japan and China. Daisensui Pond, containing the islands Horaijima and Chikubujima, was both the ocean and Lake Biwa. Recreations of renowned beauty spots instantly recognizable to educated people, such as the Shiraito Falls at Mt. Fuji and Hangzhou's West Lake, were positioned cleverly around the garden, though naturally scaled-down due to space restrictions. These shrunken landscapes are known as shukkei. Enclosed, scaled-down visions of Eden are the basis of Japan's particular approach to garden design.

Rikugien, created almost 70 years after Koishikawa Korakuen, contains scaled-down landscapes such as Deshio-no-minato and Fujishiro-toge from the “Eighty-eight famous scenic spots” celebrated in the Manyoshu and Kokin Wakashu poetry anthologies. Rikugien is a waka poem theme park, its methodology identical to that of Disneyland or Universal Studios: only the theme is different. In the embrace of his garden, its creator, cultured in things Japanese and Chinese, recreated his ideal realm.

The Stone Wall and Moat Enclosing the Garden

The seaside residence served a similar purpose to the outer bastions of Edo castle, so the main gate was a box-shaped masugata gate built from large komatsuishi (andesite) rocks. This was indeed a battle-ready garden

Gazing up at “Star” Trees

Garden vistas are often centered on distinctive old or famous trees, such as the 300-year-old pine of Hamarikyu, the “lone pine” of Koishikawa Korakuen (see photo), and the weeping cherry of Rikugien. Each tree is a dominant player in its garden, with a story to tell.

Studying, Crossing, and Savoring Stepping Stones

Garden paths take many different forms. Stepping stones crossed cautiously step by step offer visual enjoyment in their arrangement, as do variations in walking speed and length of stride.