The History of “Okigusuri” Medicine and its “Use First, Pay Later” Concept

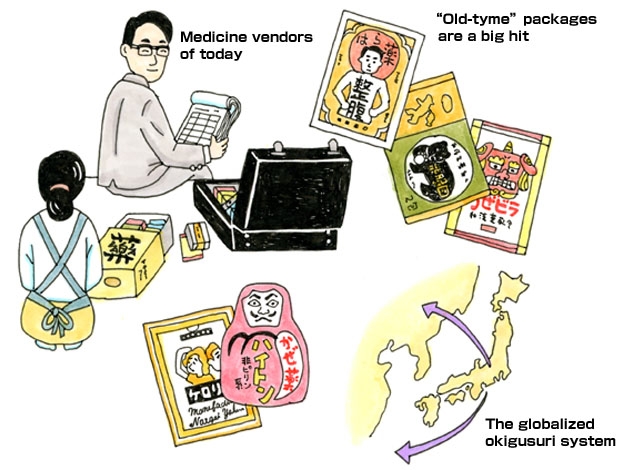

“Toyama okigusuri” refers to a unique marketing system in which a vendor leaves a medicine chest of over-the-counter items at a customer’s home on a “use first, pay later” basis. The unique arrangement, which only requires payment for medicines used, dates back 300 years in Japan, and is now spreading to other nations. The “okigusuri story” whisks us back to feudal times in Japan…

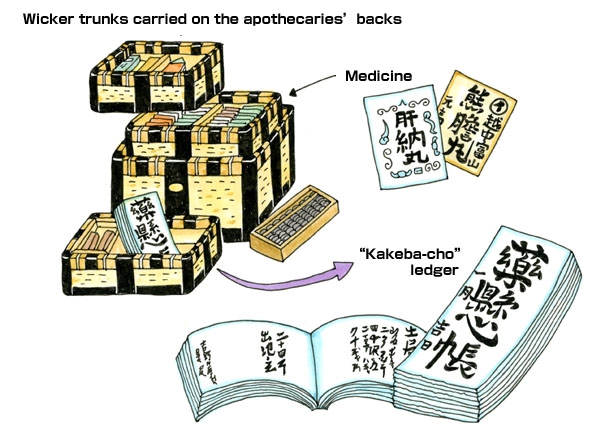

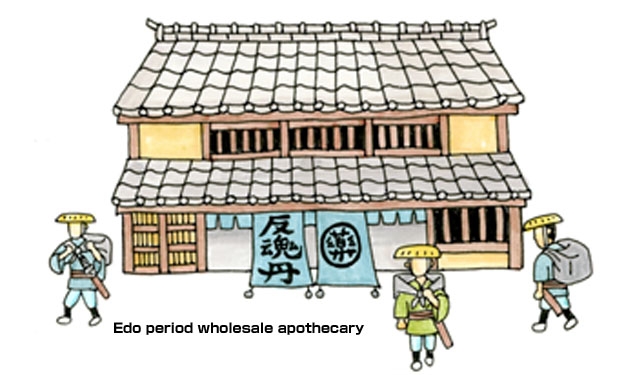

The “okigusuri business” involved apothecaries travelling the length and breadth of Japan, depositing filled medicine chests at individual homes, and returning later to replace depleted items and collect payment for products used. The system began in 1683 when feudal lord Maeda Masatoshi, head of the second fief in Toyama, took a reinvigorating “miracle medicine” known as “hangontan” entrusted to him by a doctor named Jokan Mandai from Bizen (in what is now Okayama Prefecture). The medicine worked so effectively that Lord Masatoshi henceforth always carried some in his pocket.

In 1690 on a visit to Edo Castle, Lord Masatoshi encountered Kawachinokami Akita, a fellow nobleman from Miharu (in what is now Fukushima Prefecture), who was suffering from a terrible stomachache. Lord Masatoshi shared his hangontan remedy with Akita, and the ailment vanished.

Hangontan’s curative power in the “Edo Castle Stomachache Incident” amazed the many daimyo who had assembled from near and far, and they reportedly petitioned to acquire the medicine themselves.

Hangontan’s principle effect resembled that of today’s multipurpose digestive remedies. Lord Masatoshi ordered Gen’emon Matsuiya, an apothecary doing business near Toyama Castle, to fill incoming orders for hangontan from feudal lords and their retainers. Although the legend of Lord Masatoshi may be unverifiable, there is no doubt that he encouraged the cultivation of medicinal plants and studied remedial powers of various combinations. He subsequently promoted nationwide marketing of the medicine, and the “okigusuri” business run by Toyama’s merchants expanded. That business now claims a history of over 300 years.

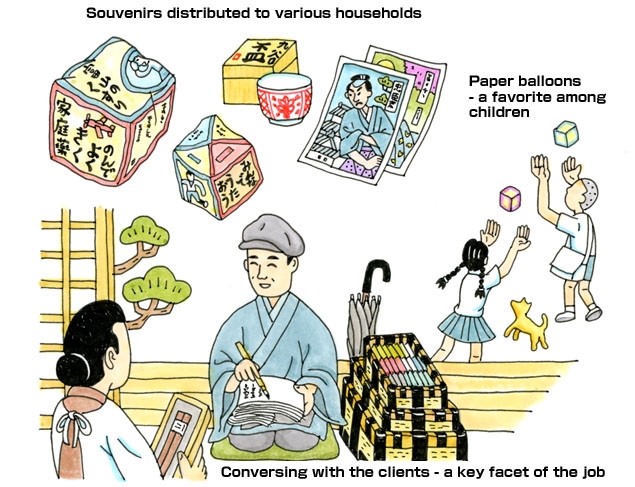

People were undoubtedly suspicious of a sudden visit from an unknown salesman. For their part, the vendors always took pains to be attentive and discreet when entering private residences for initial sales calls.

※Hangontan is sold even today, but its current composition differs from that of the Edo period.