Moss

In the West… Moss Relates to Man

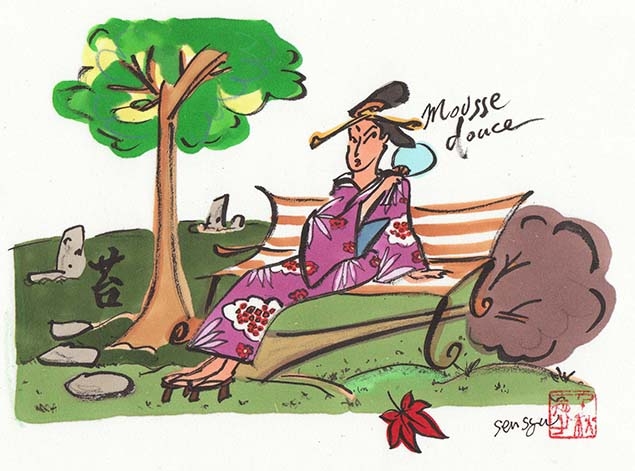

Fortunately for French poets, in French the word for “moss” (mousse) and the word for “soft” (douce) happen to rhyme. And in fact, poets and lyricists have made great use of this rhyme. Coincidence is a wonderful thing, and the fact that moss is indeed soft makes this rhyme even more convenient.

In the West, the first feeling the word “moss” arouses is a romantic one. What comes immediately to mind is a moss-covered bench. Perhaps the bench is decorated with ancient carvings, and has offered generations of lovers a place to sit and kiss, to proclaim their everlasting devotion, or to surreptitiously peruse a love letter.

It also brings to mind an image of renaissance sculptures, figures that have stood watching the march of time with perfect composure. The statues look with melancholy upon the moss and vines that surround their bases like crowns. Beginning with “Beauty and the Beast”, Jean Cocteau, who was a true poet among poets, often had benches and statues appear in the mysterious castles and gardens of his movies, objects which would move about when freed from the gaze of humans.

Another dream that moss arouses in those of us from a background of Western culture is the joy of running barefoot over, or lying down on, a carpet of moss on a hot summer day, enjoying the indescribably cool, luscious sensation. It is like plunging into an illusion of floating on velvet.

As you may already know, nouns in French are separated into either the feminine or the masculine. Mousse, which means “moss”, is a feminine noun, the perfectly appropriate gender for moss. Meanwhile “forest” (bois) is a masculine noun, and this too seems the perfect gender to describe the warm yet rugged atmosphere of a forest.

Looking now at the world of fashion, luxury brand couturiers and the stylish women who are their customers have a great fondness for the color “moss green” in their daytime wear. While it stands out more than ordinary beige, moss green is a similarly modest color, yet both bright and warm enough to provide a soothing ambience, something that beige or gray won’t do. Women, however, will only wear moss green for daytime; it loses its luster as the sun goes down. Once the clock strikes 6 p.m., women turn to gold jewelry to give them the glamour they need.

Leaving aside the costumes of high society, let us talk about moss as a plant, one which never seems to flower, but hugs the ground in a furry covering.

One might compare moss, which deepens in color and grows fuller with each passing rain, to a youthful woman’s skin, often described in Japanese as mizumizushii, or fresh and luscious.

Soft, short-stemmed moss uses its rhizoids to attach itself to the surface of things. “Rhizoid” is the academic term for a structure of fine, root-like filaments, which are responsible for the ability of mosses to live not only on the ground, but on trees, walls, and roofs, creating a uniquely pastoral, poetic aura.

Mosses prefer a shaded, damp environment, and in doing so may be looking back at their own roots. Many botanists argue that the ancestors of mosses were actually green seaweeds.

This is also why moss growing on trees will usually be found only on the north side of the trunks. When I was a child, my father taught me that, if I ever got lost in a forest, I could always find north, south, east, and west by checking on which side of the tree trunks moss was growing, because moss always grows on the north side.

Women in my grandmother’s generation also knew of the medicinal properties of moss. It can be used to relieve fevers, improve anemia, and it works as a tonic. They would collect the moss in the summer, when the color was a deep green. After drying the moss, they would store it in tightly-covered glass jars, boiling it twice before using it as medicine. It had an excellent slimming effect.

So that is the story in Europe. This goes for nature in general, but in Europe, the value of moss was first understood through the touch of human hands.

In Japan…Man Bonds with Moss

In Japan, I discovered a culture completely different from that in which I had been raised, and I immediately took to it.

I have resolved to spend my final years, and eventually be buried, here in Japan. I first began to feel this way when I found myself at standing in front of a small cemetery laid out next to one of the sub-temples at Daitoku-ji, gazing at gravestones on which moss had grown to become almost a part of the design.

Arriving in Japan decades ago, encountering the aesthetic of the Japanese garden was, for me, a truly shocking event. It is an aesthetic created out of plants, moss, stones, and sand, all brought to the peak of their natural beauty.

There, I could feel the care taken in the details, and later, I found the same aesthetic in Japanese literature as well. A classic example is in Natsume Soseki’s “Kusamakura”, which in its opening discusses the contrast between reason and emotion. Natsume seems to believe that emotion is more important than reason, or at least, that emotion is the less dangerous of the two.

My first visit to a Japanese garden was on October 30 of a certain year. The leaves of the maple trees had just begun to turn, and a few of them had fallen onto the moss below, creating a tapestry-like display. This picture, entirely at the hand of nature, was as fine as any work created by the greatest artist. My mother, who was visiting Japan at the time—she was a painter—saw this and said “This is the work of God.”

Long before my mother said those words, Sen no Rikyu felt the same way.

Japanese gardens are austere, but at the same time highly refined. This refinement is the opposite of ostentatious flamboyance, and is a reflection of the Japanese aesthetic sense which says “The shadow cast by a tree is more beautiful than the tree itself.”

In Japan, moss is loved for itself, for its fragile beauty that lies hidden in the shade. The best way to experience the allure of that refinement is to visit Kyoto’s Saiho-ji (Kokedera, or Moss Temple).

In Japan, moss carries a special meaning, representing the concepts of simplicity, humility, and refinement, which in turn lead to a sense of wonder, a pang of nostalgia, and at times even bringing a feeling of loneliness and resignation.

Moss also exemplifies modesty. For the Japanese, modesty is something they are born with, something which they take care to nurture and which they hold as a basic principle in life.

This is a way of looking at the world that is unfamiliar in the West. Shinto, a uniquely Japanese religion deeply ingrained in Japan’s culture, believes that faith resides in nature itself, and is not something created by man, as in the West. Evidence of this can be seen in the fact that the Japanese build gardens, rather than cathedrals. Gardens teach us that all things change. Buddhism, as well, has had an effect on Japanese gardens and the mosses that grow in them. To meditate in front of a moss garden is to accept time moving at a slower pace, because waiting for moss to grow in a garden requires a great deal of patience, and thereby wisdom.

Once one understands how the Japanese people interact with nature, one can look at how the citizens of Japan have reacted to the recent tragic disaster with such dignity and fortitude, and see that moss truly represents the Japanese mind.

*This article was originally posted on JQR.