Passion and technology behind English sumo coverage

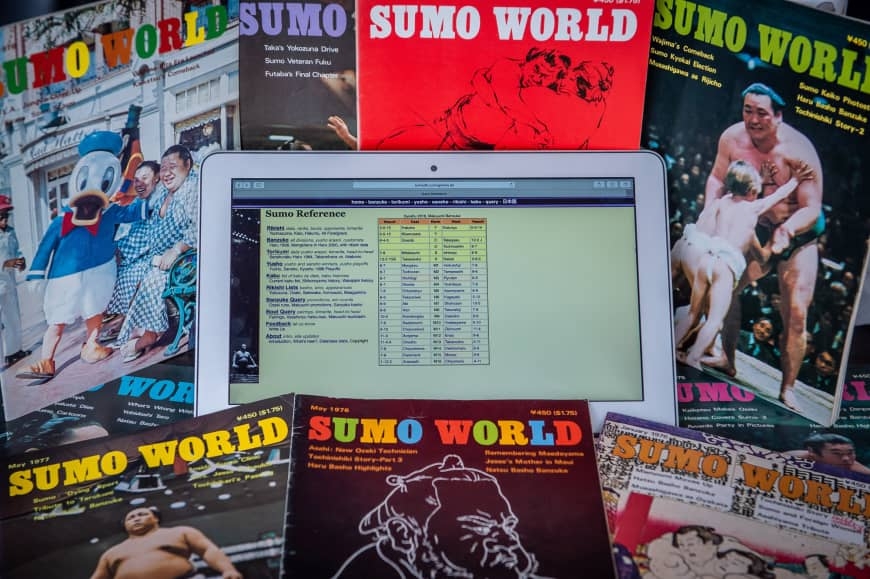

The fan-published magazine Sumo World and websites such as Sumo Reference have enabled foreign fans of the sport to follow the latest news in detail from abroad. | JOHN GUNNING

Sumo fans around the globe are spoiled for choice these days when it comes to following their favorite sport.

Livestreams, tournament preview shows in English, ever-increasing coverage in mainstream media and a plethora of fan sites and blogs are all available.

It’s a far cry from 15 years ago, when even basho results were hard to come by, never mind in-depth analysis.

Go back a couple of decades and foreign fans’ only source of information was a bimonthly magazine put together by Japan-based sumo fans and mailed out worldwide.

Established in the early 1970s, Sumo World was a mix of tournament reports, interviews, full-length features and opinion pieces.

For thirty years it was an indispensable publication for veteran fans and newcomers to sumo alike.

The magazine though, like many others, failed to adapt to the rise of the Internet, and when subscribers started getting issues late (or not at all) in the early 2000s, Sumo World quickly faded from relevance. It still publishes an occasional issue, but that can only be found at the temporary bookstore set up inside the Kokugikan during Tokyo tournaments

An email mailing list gave people a chance to exchange views and opinions with like-minded others. When online message board Sumo Forum started in 2004, things really kicked into high gear.

The forum, which for many people remains the primary source of sumo news in English, is an eclectic mix of sumo insiders, hardcore fans, rikishi, media members and people with backgrounds in data and information processing.

The latter is important because their presence helped explode many of the old myths about the sport.