With fortunes waning in Japan, sake finds a new home abroad

Sommelier Xavier Thuizat thinks the amino acid in sake makes the beverage a perfect match for French cuisine. | COURTESY OF KURA MASTER

Xavier Thuizat has a pretty clear idea of what doesn’t go well with sake.

“I think the worst pairing with sake is sushi,” says Thuizat, head sommelier at Hotel de Crillon, a historic luxury hotel in Paris where Marie Antoinette once lived. “Why? Because it’s rice with rice. Do you want to eat grapes with wine?”

Instead, Thuizat prefers to pair a kimoto-style sake with a dish of volaille de bresse chicken in a creamy sauce, or a yamahai-style sake with some French cheese.

Thuizat thinks the amino acid in sake makes it a perfect match for French cuisine and, since selling 2,500 glasses of the drink in his first year in his previous job as head sommelier at the five-star Peninsula Paris, he has been on a mission to make the iconic Japanese beverage a regular feature on French menus.

Since 2017, Thuizat has been organizing Kura Master, an annual sake contest in Paris that sees leading sommeliers and other wine professionals in France judge sake based on how well it goes with French food.

His efforts appear to be paying off. Imports of Japanese sake to France are currently at record levels, with sales reaching $2.6 million in 2019 — more than four times the figure 10 years previously.

Thuizat admits that many French consumers had a few doubts at first, but he believes sake has the potential to become a truly global product.

The quality of sake produced by small craft breweries overseas is being recognized by leading brewers in Japan. | COURTESY OF ZENKURO

“It’s more difficult because France is a wine country,” Thuizat says. “But sometimes people want to drink something different for a change. Wine is very easy to find. There are many wine shops in Paris and many restaurants. Sometimes people want to drink something new. They want to be surprised. They want to learn something different. That’s why I believe in the future of sake.”

France is not the only country that has been importing more sake from Japan in recent years. According to figures provided by the Japan Sake and Shochu Makers Association, sales of exported refined sake have risen over each of the past 10 years, more than tripling from ¥7.2 billion in 2009 to ¥23.4 billion in 2019. The biggest export market is the United States, which bought ¥6.76 billion worth of sake in 2019, followed by China with ¥5 billion and Hong Kong with ¥3.94 billion.

An increasing number of overseas consumers, including the guests at Thuizat’s hotel, are beginning to discover that sake is a versatile drink that goes well with many different types of food. The real driving force behind its growing global appeal, however, is the expanding reach of Japanese cuisine.

According to a Ministry of Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries survey released in December last year, the number of restaurants serving Japanese food overseas increased by around 30 percent in just two years between 2017 and 2019, and 50 percent in Asia alone. There were around 156,000 restaurants serving Japanese food outside Japan in 2019, compared to just 24,000 in 2006.

More small craft sake breweries such as New Zealand’s Zenkuro have opened in a diverse range of countries around the world in recent years. | COURTESY OF ZENKURO

As the world’s hunger for Japanese food grows, so does its thirst for sake. With consumers in many countries still comparatively new to the drink, however, there are still obstacles to overcome before it can gain a firm foothold in overseas markets.

“There’s a misconception that it’s distilled and, if it’s distilled, then it’s strong,” says David Joll, head brewer at the Zenkuro sake brewery in Queenstown, New Zealand.

“There’s a misconception that it’s 30-40 percent alcohol,” Joll says. “You drink it as a shot and you’re going to get a headache from it. I guess that’s the main one. I think it comes from bad experiences people have had with drinking too much. Until recently, the sake they had in New Zealand wasn’t very good quality. People had some bad experiences and blamed it on the sake.”

Hidetoshi Nakata had a similar impression of sake when he was the star player for Japan’s national soccer team in the 1990s and 2000s. He thought it was a drink for “older people and drunk people,” and he preferred the local wines he enjoyed during his seven years in Italy playing for clubs like Perugia, Roma and Parma.

Then, when he came back to Japan in 2009 following his retirement from soccer, Nakata had an epiphany. He began touring the country to learn about traditional Japanese culture, and visited craftsmen, farmers and sake brewers to find out more about what they did. He emerged seven years later with an intimate knowledge of Japanese crafts, and decided to use what he had learned to help the sake industry.

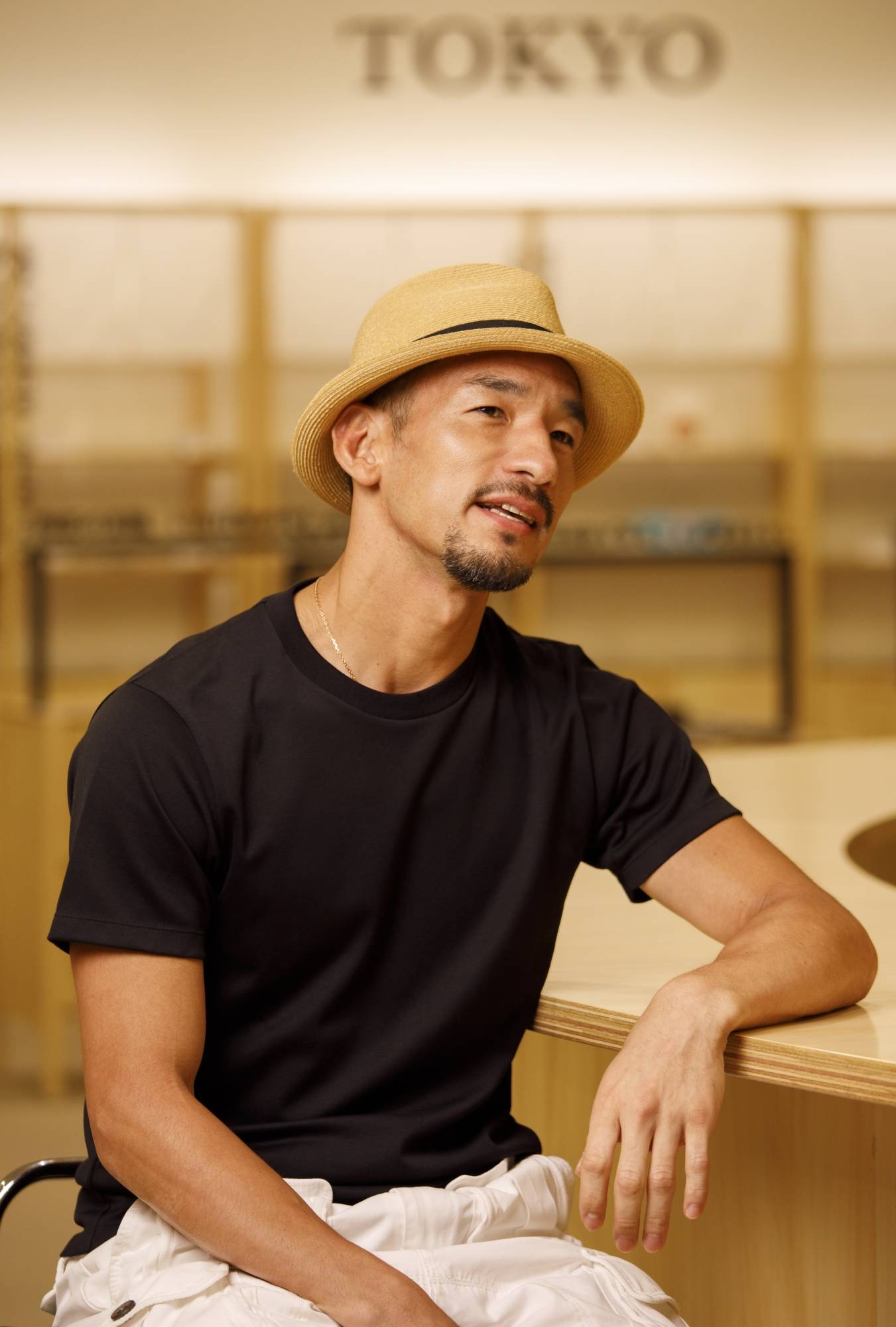

Former soccer star Hidetoshi Nakata is involved in a range of ventures to help sake become a genuinely global product. | MARTIN HOLTKAMP

Nakata has since become something of a sake evangelist, and his company, Japan Craft Sake Company Co, Ltd., is involved in a range of ventures to help sake become a genuinely global product. As one of Japan’s most internationally recognized personalities, Nakata has helped to raise sake’s profile significantly. His involvement, however, goes much deeper than that.

Nakata’s company has developed an app called Sakenomy, which gives users information about a bottle of sake, including where it was made, details about the producer and what food it goes well with, simply by scanning the label, many of which feature heavily stylized kanji characters. An upgraded version of the app was launched on Oct. 1, and Nakata believes it provides a much-needed service.

“If you look at sake bottles, even if you’re Japanese, you can’t really read them,” says Nakata. “For people from overseas, it’s impossible. The product can be very good, but if you can’t read the name on the label, how can you order it or buy it? Lack of information is a big problem. Even now, if you ask people, most people know fewer than 10 brands. Most people ask the chef to choose a good sake, or they go just by price. That’s the reason why I want to provide people with good information, so they’re able to select a sake that best suits them.”

Nakata is keen to address other areas in which he sees flaws in the sake market. As a player in Italy, he discovered that Italians think of sake as a drink always to be consumed warm. He later learned that this is because premium sake is at its best when it is kept at a temperature of minus 5 degrees Celsius, but the lack of refrigeration when bottles are being transported overseas means the product’s quality has already deteriorated by the time it reaches its destination. In such a condition, drinking it warm is the only way to make it palatable.

Nakata aims to solve this by helping to create an improved export and logistics system, and he has also developed a refrigerated unit for shops and restaurants to store their bottles at the correct temperature, which was released last year. Additionally, he has been working on a system in which every sake bottle is given a unique code that can be checked to verify the product’s origin, condition and authenticity.

“From a brewery point of view, once they sell to a sake shop, they don’t know where their sake goes after that, so they don’t have any marketing data,” Nakata says. “By using sake blockchain, they know which country their sake is in, which restaurant is selling their product. You can track any sake. Breweries will be able to gather marketing data and then think about next year’s production. What kind of flavor profile would be good for that particular country? They will know.”

Not every bottle of sake is made in Japan. In recent years, a growing number of small craft breweries have appeared in a range of countries as diverse as Norway, Mexico and Spain, and their quality is being recognized by the sake establishment.

David Joll, head brewer at the Zenkuro sake brewery in Queenstown, New Zealand, works on a batch with the help of Yasuko Shikomi. | COURTESY OF ZENKURO

Joll and his two partners founded Zenkuro — meaning “all black” in Japanese, a nod to the New Zealand national rugby team — in 2015. Joll had spent his entire adult life either living in Japan or with some connection to the country, and he was looking for a new project after returning to Queenstown. He and his partners decided to try making sake, so Joll returned to Japan to take a professional course before spending time observing methods at breweries in Ibaraki Prefecture and Canada.

Joll then went back to New Zealand and started brewing in his garage, but he encountered several early problems. He couldn’t find much information in English, he couldn’t buy the variety of rice he wanted and he couldn’t get his hands on any kōji — the rice mold needed to make sake.

The partners persevered and, after moving to bigger premises, they began producing some interesting results. The organizers of the London Sake Challenge, Europe’s oldest sake contest, invited Joll and his colleagues to send some of their produce to the 2016 competition, so they entered a drip-press junmai and a nigori. To their surprise, they won a gold and a silver medal.

“The idea was just to get some feedback from experts outside of New Zealand,” Joll says. “The London Sake Challenge attracts probably 95 percent Japanese breweries. At that time, there were only a couple of non-Japanese breweries anyway. There are now probably about 30 craft, small-scale breweries around the world, but back in 2016 there were only a few.

“It gave us a little bit of credibility, and a reward for our efforts,” he says. “It was encouragement for us that we weren’t wasting our time.”

The Japan Sake and Shochu Makers Association says it supports the efforts of overseas sake breweries, and sees them as allies helping to spread the word rather than rivals to Japanese producers. While sales of sake are taking off around the world, however, the picture does not look so healthy at home.

Domestic sake sales have been falling since the 1970s and, although the decline has largely leveled out since the early 2010s, the current market is about one-third the size of 50 years ago.

Hitoshi Utsunomiya, director of the Japan Sake and Shochu Makers Association, believes many people in Japan know little about sake because it has ‘disappeared from homes.’ | ANDREW MCKIRDY

Japan Sake and Shochu Makers Association Director Hitoshi Utsunomiya points to a number of factors, with the growing popularity of shōchū, the overall decline in alcohol sales and an aging population all contributing to sake’s waning fortunes. Softening the blow is the fact that the market for premium-grade sake has grown in recent years, and the average price of sake has increased sharply since 2012.

Utsunomiya says many people in Japan know little about sake because it has “disappeared from homes,” but he also believes such a blank canvass could work to its advantage.

“Young people don’t really know much about sake, but there is a new generation, including young sake brewers, which has started to spread the word to young people,” Utsunomiya says. “There are fewer young people nowadays who think of sake as a drink for old people. The price of sake has gone up, so young people tend to think of it as an expensive drink, something high quality and complex.”

Sake festivals like Nakata’s Craft Sake Week are trying to harness this growing interest among the younger generation. First held in 2016 in Tokyo’s Roppongi Hills, the event brings together chefs, designers and DJs to create a glamorous setting for guests to try sakes from selected breweries. Last year, it attracted around 200,000 people.

“I thought we had to change the image people had,” Nakata says. “At that time, there were so many sake events, but most of them were for hard-core enthusiasts and people that only go to drink a lot for a cheap price. We have to change this image. We have to select the best sake and the best restaurants and create a great atmosphere.

“Of course, most of the people who come to the event don’t know about sake and how to choose one that suits them, so that’s why instead of bringing 100 bottles, we bring only 10 breweries every single day. People can try them and remember them. That’s the most important thing.”

Former soccer star Hidetoshi Nakata is involved in a range of ventures to help sake become a genuinely global product. | MARTIN HOLTKAMP

Like most events in Japan, this year’s Craft Sake Week was canceled because of COVID-19, and the pandemic has impacted the sake industry in many other ways. Utsunomiya says makers of premium sake, who mainly sell to bars and restaurants, saw their sales drop to about half the normal level earlier this year, while makers of sake for general consumption, who mostly sell to supermarkets, took only a marginal hit. Overall, Utsunomiya says, sales are down by around 20 percent.

The pandemic has also damaged the sake industry’s efforts to make the most of Japan’s tourism boom. Tours of sake breweries had been growing in popularity, and the Japan Sake and Shochu Makers Association had been involved in organizing seminars and tastings geared toward overseas visitors.

Nakata says the domestic market is already beginning to show signs of recovery, however, and he believes that Japanese cuisine is established enough overseas for sake exports to weather the storm.

Sommelier Thuizat, meanwhile, finished judging this year’s Kura Master competition in Paris last month. From 824 entrants, the judges awarded 84 platinum medals and 188 gold medals across six categories.

Thuizat says he and his fellow judges have come to know sake very well now that the event is in its fourth year, and he is as excited as ever at sake’s potential to pair with French food.

“The final result is very different from the International Wine Challenge,” Thuizat says. “We find more intense, full-bodied sake in Kura Master. At IWC, we see more sweet sake, purer sake. We love yamahai in France because yamahai and cheese is a perfect combination. That’s why I think the Japanese breweries love Kura Master, because it’s a different result and a different way of tasting.

“French customers need to make a link with cuisine once they find new beverages,” he says. “It was difficult at the start in France, because French people couldn’t imagine that Japanese sake could make a link with French cuisine. Now they know that.”

Kura Master is an annual sake contest in Paris that sees leading sommeliers and other wine professionals in France judge sake based on how well it goes with French cuisine. | COURTESY OF KURA MASTER