Masters of their craft: Foreign apprentices reveal their life-changing experiences in Japan

Traditional lacquerware artist Suzanne Ross at work in Ishikawa Prefecture | COURTESY OF SUZANNE ROSS

An apprenticeship in a traditional Japanese craft can be daunting for even the keenest student. Often lasting years and with few vacation days, the commitment requires unwavering endeavor and patience, without even the guarantee of a lifelong livelihood on completion. Many of Japan’s crafts are in decline, offering artisans an uncertain future.

For a foreign national, then, the path to apprenticeship and beyond — to employment or self-employment — can seem impassable. Not only is the craft new and often unlike anything experienced before, but the language and culture of the teaching environment is unfamiliar.

Still, more and more people from around the world are embracing the challenge and carving out a place for themselves in Japan’s oldest industries. Many are determined to turn their passion into a job, either in Japan or their home country, and to help future-proof their much-loved craft.

British urushi (Japanese lacquerware) artist Suzanne Ross, 58, has dedicated almost all her working life to the pursuit and preservation of her craft.

Her specialty is wajima-nuri, one of the country’s most renowned and respected lacquerwares, which dates from the 14th century to the 16th century and has more than 100 stages of production.

Traditional lacquerware artist Suzanne Ross outside her gallery in Wajima, Ishikawa Prefecture | COURTESY OF SUZANNE ROSS

“In my naivety, I thought I could master the art of urushi in three to six months and am now here 36 years,” Ross says from her studio in Wajima, Ishikawa Prefecture, the home of wajima-nuri. “It’s not something you can master in a lifetime, which is probably true for all traditional Japanese arts. You don’t master them, they master you, and it’s a very humbling experience.”

Ross arrived in Japan in 1984 to learn urushi, a craft that had captured her interest during a visit to a Royal Academy of Arts exhibition in London. During a three-year stint teaching at an English language school in Nagano Prefecture, she traveled to Wajima annually to ask companies for an apprenticeship.

The first response was that, as a woman, she could do only sanding, the step to prepare the surface before subsequent layers of lacquer. The second time, she was told her Japanese was inadequate. Finally, she was referred to a local lacquerware school, the Wajima Institute of Lacquer Arts.

In courses spanning nine years, as well as one year’s tutelage under a Living National Treasure, Ross learned how to make urushi items from start to finish, a rare feat as artists tend to be highly specialized due to the division-of-labor production method. Her reasoning was that she could return to England as an urushi artist if she were self-sufficient, and she resolved to complete her training despite the culture shock she faced.

“It was completely the opposite (to how I was taught art in London),” she says of the experience. “You are discouraged to ask why. Without understanding the reason behind what I was doing, I couldn’t master the techniques.”

Much of her confusion lay in why each master taught the same techniques in different ways. In time, however, she realized that after mastering the basics, urushi artists must find their own methods that suit them and their artistic goals.

“Craft is not something you’re spoon-fed. It’s a discovery, a voyage,” she says. “You try things and you fail and then you learn from that failure. Learning by experience is a very valuable thing.”

And her learning continues even today. Her portfolio includes vessels incorporating lace, washi paper and silver, as well as more modern items such as fine art and jewelry. Ross hopes the latter will spark interest in urushi among younger generations, which she says is vital to stop the decline of the craf

Some examples of Suzanne Ross' urushi jewelry | COURTESY OF SUZANNE ROSS

“Urushi is suffering more than other crafts,” she says, adding that the tools and materials are expensive, while the craft is difficult and time-consuming. Although she does not think the craft will disappear, she is concerned because traditional techniques cannot be written down, only passed verbally from craftsman to apprentice.

“We can’t lacquer the way we did in the Edo Period (1603-1868) because we don’t understand some of those techniques,” she says. “Now, again, the standard is going to drop.”

To help combat that, Ross has spent the past 20 years traveling nationwide and abroad to share her expertise on urushi via lectures at universities and artistic centers, artist-in-residence programs and media appearances. She has even planted urushi trees, which are in short supply in Japan.

Her motivation has been to encourage Japanese people “to appreciate their own culture so they preserve it for humanity.”

Traditional plasterer Emily Reynolds squats beside the first plaster work she completed. | COURTESY OF EMILY REYNOLDS

Emily Reynolds, who is learning traditional plaster craft in Kyoto, shares Ross’ belief that Japan’s historic crafts have value for the world.

A fan of earthen construction because of its low environmental impact, the American apprentice says Japan has the potential to change the image of earthen buildings as bulky or dirty structures. The walls of shrines, temples and teahouses — which are typically earthen — are thin, clean, durable and structurally sound, providing a “good case study for architects,” she says.

Reynolds is in the fifth year of a plastering apprenticeship, currently part-time, while she undertakes a doctorate at Kyoto Institute of Technology. Her work focuses on the restoration of temples, residences, shrines and cultural properties and utilizes only traditional materials. It took one year for her to find the position; she rejected other plasterers’ unions in other prefectures due to their adoption of cement and other industrial materials.

Plastering, Reynolds says, “comes with history and lineage. Every generation passes on whatever they learned to the next generation. It’s an enormous assimilation of knowledge that becomes obsolete when plastering becomes (the use of) a bag of stuff and water.”

Traditional plasterer Emily Reynolds at work | COURTESY OF EMILY REYNOLDS

In recent years, more and more craftsmen have come under pressure to use new materials as they are quicker to dry than natural materials. For many, though, the transition is far from easy. According to Reynolds, traditionally trained plasterers struggle to make materials based on a formula rather than touch and instinct.

Shikkui lime plaster that is used for temples and castles, for example, has four ingredients: lime, hemp fibers, seaweed glue and water. Each producer and company, even each plasterer, has a preference about the components, such as the type of lime, length of fiber and volume of seaweed. Furthermore, shikkui recipes differ in summer and winter as the climate affects the drying speed.

Reynolds is proficient in making shikkui and applying it at a thickness of 1.5 millimeters, but says thinner layers require more precision and expertise than she may ever obtain. By working only three days a week, she tends to miss key stages in each job and cannot learn solely by muscle memory.

Still, she recognizes that she is lucky to have training in the craft and hopes to share it with as many people as possible via her Facebook group, Japanese Plaster Craft. With more than 1,000 members hailing from the Americas, Europe and Asia, interest in traditional plaster is growing outside Japan.

“I love seeing how people are getting inspired and are trying to make their own shikkui,” she says. “And I hope (my colleagues) enjoy having me as a cheerleader for the industry.”

Bonsai artist Valentin Brose works on a forsythia for a customer. | COURTESY OF VALENTIN BROSE

Valentin Brose, a bonsai artist based in Germany, is also hopeful about the future of his craft. Although bonsai in Japan is dominated by an older generation that sometimes struggles to find successors for their nurseries, more young people in Europe are taking up bonsai as a hobby or job, he says. Most cities have bonsai clubs or nurseries, and many people are skilled, having joined workshops led by Japanese masters or Japan-trained masters.

Brose runs workshops at his bonsai garden, near Stuttgart, which is home to more than 200 trees that he owns and maintains. Teaching the art of bonsai is one of his main activities alongside giving seminars, importing trees and working on commissions for clients. It is also an activity he enjoys as he can “spread his love of bonsai.”

The popularity of bonsai is evidenced by his growing business and the increasing number of requests he receives to travel for work, including to places such as Switzerland, France, Belgium and Austria.

Bonsai artist Valentin Brose waters a tree at Shunkaen Bonsai Garden in Tokyo. | COURTESY OF VALENTIN BROSE

Brose attributes his success to his three-year apprenticeship under renowned master Kunio Kobayashi at Shunkaen Bonsai Museum in Tokyo from 2008, which he sums up as a “very difficult but indescribable, wonderful experience.”

Unlike his previous apprenticeship as a gardener in Germany, he was faced with 12- to 15-hour workdays, a strict hierarchy and heavy responsibilities. Training was in Japanese only and apprentices were expected to learn by watching rather than by explanation. All apprentices ate together and shared lodgings near the garden. Newcomers were assigned to serve tea, clean and assist, before one of the masters assessed their work and allowed them to help with progressively important trees.

Despite the hardships, Brose says he learned a lot from the experience, both professionally and personally.

“I learned that I had to be humble — that’s the big difference to an apprenticeship in Europe — and I learned that you are never finished learning,” he says, adding that he also picked up life lessons like avoiding waste as well as respect for people and the environment.

Carpenter Dale Brotherton works on a teahouse. | COURTESY OF DALE BROTHERTON

Dale Brotherton, owner of Seattle-based Japanese woodworking business Takumi Co., had a similar experience while apprenticing from 1978 to 1985 with a traditional carpenter recently relocated from Kyoto to California.

“I had to learn from watching. When (my master) thought I’d gotten far enough that I could absorb a little more, he’d show me a bit more and I’d try and do that,” he says. His teacher also sought to impart social values and a way to approach life, to fulfill his “obligation” to his student.

Brotherton says he embraced the offer and “dove into (everything) wholeheartedly.”

An interior by carpenter Dale Brotherton | COURTESY OF DALE BROTHERTON

He undertook a wide variety of work, from doors and window frames to tea rooms in Japanese gardens, practicing his techniques repeatedly until he could move and hold tools like his teacher. His training, he says, was both mental — comprehending tasks and figuring them out — and physical: getting the body used to moving in new and specific ways.

After six years, he felt comfortable with the carpentry tasks he had learned and moved to Nagano Prefecture to gain more experience in building houses. He soon found that carpentry in Japan was highly specialized and sub-divided; he even caused a stir by making his own wooden toolbox.

For each job, framers would cut out the house frame using hand-controlled machinery and put it up, leaving another crew to do the finishing. Today, he says, “the trade of carpentry in Japan has diminished” as most house frames are cut out by machine in factories and simply assembled on site. That is one reason he offers workshops on Japanese carpentry skills alongside construction for clients.

“I’m committed to offer people the opportunity to do what I do because I enjoy it so much,” he says. “I want to keep the craft alive, and workshops are a way to do that to some degree.”

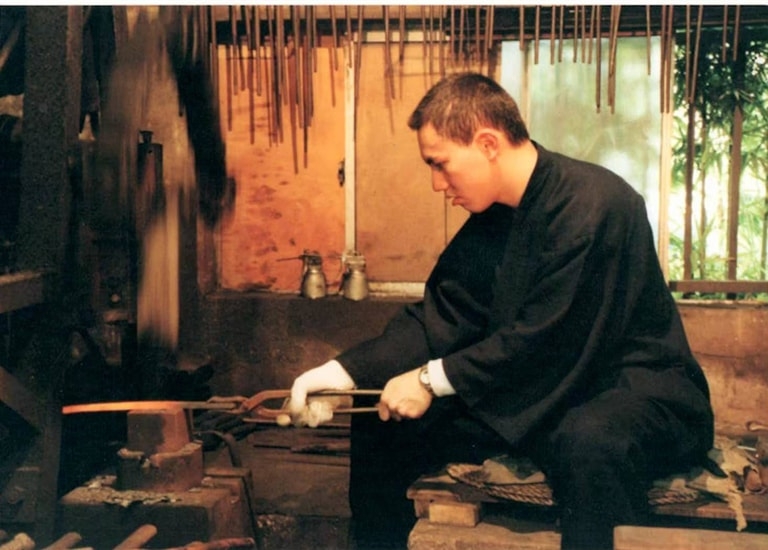

Ron Chen specializes in every aspect of high-quality sword making and repair. | COURTESY OF RON CHEN

Ensuring the future of his craft is also the motivation of Ron Chen, a Taipei-based craftsman of nihontō (traditional swords). He specializes in every aspect of high-quality sword making and repair, enabling him to work on demand for his growing client base in the United States and Europe. Most requests are from people with sword collections or who practice martial arts like iaidō.

Chen developed forging skills at his father’s factory before apprenticing under legendary swordsmith Yoshindo Yoshihara in Tokyo and returning to Taiwan to set up his own workshop. Like many other foreign specialists in Japanese crafts, he is skilled in every aspect of his craft, from handling iron to decorating the scabbard with urushi.

With modern-day nihontō dating from the Heian Period (794–1185), Chen follows in the footsteps of a long line of craftsmen, including those who fought for the preservation of the Japanese sword when a ban on nihontō production during Japan’s post-World War II Occupation threatened the craft with extinction.

Today the craft continues to attract new interest but there are believed to be only 300 swordsmiths active in Japan compared to thousands some years ago, according to Chen. Having experienced the joy of learning nihontō, he is passionate about the need to preserve it and other Japanese crafts.

“One of the best things about Japan is its traditional skills,” Chen says. “We must not lose the ethos and culture associated with those skills.”