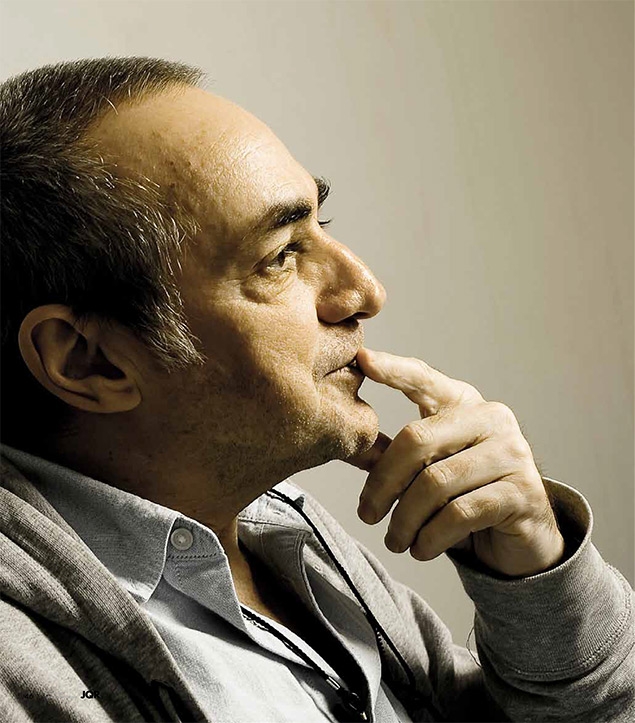

Film director, Claude Gagnon

Japan may look very different but little of substance has changed

While he was in Tokyo, Claude Gagnon accepted JQR’s invitation to explain his love affair with Japan.

Time was, if you were a 20-yearold Quebécois intellectual, you went to France. But I never wanted to do the same as everyone else. I wanted to find the country that was the most removed from my own experience, be it culturally, religiously, philosophically, or geographically.

In the sixties, I left the séminaire (Catholic high school in Quebec) where I was studying the cours classique (classical humanities curriculum) to make movies.

Then in 1968, wanting to discover the world outside books, I hitchhiked to Mexico to visit the country during the Olympics. Strangely, it was during that trip that I realized that I knew next to nothing about the U.S.A. What I did know about it was what I’d read in books. At the age of 18 meeting a black guy who takes you to the other end of a bridge and gives you $5 out of charity after you’ve spent the night in a prison cell because you didn’t have anywhere else to sleep really didn’t match up to anything I’d ever read. You might have read Sartre and Camus, and you might think you know it all, and then you get out into the real world. Everything that I thought I knew about Americans was either wrong or only partially true. In the Deep South, a pickup truck stopped to give me a lift. The driver was a real man wearing a cowboy hat and packing a rifle.

He looked askance at my beard and the hair that I wore fashionably long. Still I was lucky because I was a sportsman and a big American football fan, and when he asked me about a Texan player in the Canadian League, I immediately replied, “Oh, he’s my favorite!” He was a little mollified. He dropped me off at a barber’s and gave me a few bucks so I could get a haircut! I went up onto the barber’s porch but I hid until my benefactor had driven off! I just wanted to explain how this experience completely changed my perception of how we see other people and of how other people see us.

I like to smash social expectations

Japan was perfect for me

It was after I’d finished traveling that I knew I wanted to make movies. I needed to know a bit more about people and not just from books but also from real life‒‒ to meet them and find out about their daily lives. It was then that I decided that Japan was probably the best place for me: an island, mountains… Canada is a new country but Japan is thousands of years old, and being here it really helped me to find myself. I first came here in the seventies. My original plan was to spend six months in Japan, and then to go to Indonesia before heading to Europe. I thought I’d do my little trip like everyone else did in those days. But after six months I still didn’t understand a thing. There were very few foreigners living in Japan in those days, and I remember that if you saw a Westerner in Kyoto, you’d crossed the road to say hi and trade phone numbers. It was the era of “Peace and Love”‒‒euphoric and stimulating.

When I’m not on a movie set, I’m actually quite shy. Even going to buy something at a store makes me feel a bit uncomfortable, so I really liked the shyness of the Japanese. And I’d come face to face with an ancient culture, of which I knew nothing at all. But rather than being frustrated, I found it very stimulating. It made me question my own experiences, find new ways of thinking, and develop new aesthetic sensibilities. Then after Keiko became a hit, I began to feel I was beginning to become bogged down and that I was becoming too comfortable. I had two kids, and my life was settling down to a dull family routine. Professionally, I was suddenly getting a lot of offers, but to make another Keiko‒‒to go back over something in which I was no longer interested. I began to panic and thought about going back to Quebec.