PEOPLE

Donald Keene reflects on 70-year Japan experience

March 20, 2019

Tokyo, which had burned during the war, has arisen from the devastation over the past 70 years. | KYODO

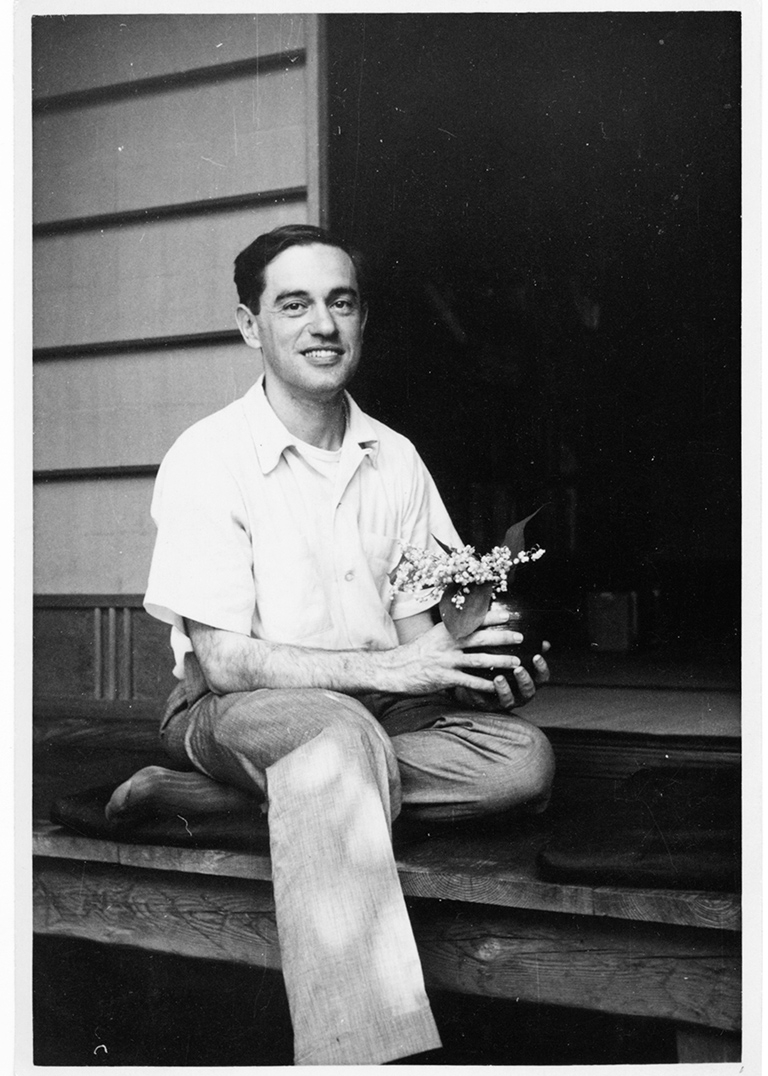

2015 marks 70 years since Japan's defeat in World War II. Renowned writer and prominent U.S.-born Japanese literature scholar Donald Keene, 92, looks back on Japan's postwar period, which he saw firsthand.

My first visit to Japan was very short, only a week or so in December 1945. Three months earlier, while on the island of Guam, I had heard the broadcast by the Emperor announcing the end of the war. Soon afterward, I was sent from Guam to China to serve as an interpreter between the Americans and the Japanese military and civilians.

After four months, I received orders to return to my original command. I was aware that the original command was in Hawaii, but when the plane from Shanghai landed at Atsugi I felt a strong desire to visit Japan. Every day during the previous four years, ever since entering the U.S. Navy Japanese Language School, I had thought about Japan. I yearned to see it, but I was afraid of being caught if I violated orders. In the end, I persuaded myself that, now that the war had ended, my crime, if detected, would be treated as minor. I informed a naval officer at Atsugi that my original command had moved to Yokosuka. He believed me and I was safely in Japan.

The drive from Atsugi was bleak. As the jeep approached the city of Tokyo, buildings grew steadily fewer until all that were left were smokestacks and sheds. Once in the city, I found the building where the other interpreters were quartered, and was told by my friends that there was an empty bed. They described the destruction they had seen in various Japanese cities, but they had not yet realized the terrible significance of the atomic bomb.

They all agreed that it would take at least 50 years for Japan to recover its pre-war status. Nobody spoke of a possible revival of Japan. This may be why only 20 or 30 of the thousand or so young men trained in Japanese by the Navy and Army attempted to find a career which involved knowledge of the language.

My second visit to Japan was in 1953, this time in Kyoto as a graduate student. I chose Kyoto not only because of its history, but because it had escaped bombing. My wartime friend, Otis Cary, then teaching at Doshisha University, found an ideal place for me to live. I intended to study at Kyoto University, but in fact, I did not spend much time there because the professor so seldom appeared. As it grew colder in the unheated classroom, I felt less and less ready to wait in vain for the professor, and was glad to spend my time in Kyoto sightseeing instead of shivering in a classroom.

My first visit to Japan was very short, only a week or so in December 1945. Three months earlier, while on the island of Guam, I had heard the broadcast by the Emperor announcing the end of the war. Soon afterward, I was sent from Guam to China to serve as an interpreter between the Americans and the Japanese military and civilians.

After four months, I received orders to return to my original command. I was aware that the original command was in Hawaii, but when the plane from Shanghai landed at Atsugi I felt a strong desire to visit Japan. Every day during the previous four years, ever since entering the U.S. Navy Japanese Language School, I had thought about Japan. I yearned to see it, but I was afraid of being caught if I violated orders. In the end, I persuaded myself that, now that the war had ended, my crime, if detected, would be treated as minor. I informed a naval officer at Atsugi that my original command had moved to Yokosuka. He believed me and I was safely in Japan.

The drive from Atsugi was bleak. As the jeep approached the city of Tokyo, buildings grew steadily fewer until all that were left were smokestacks and sheds. Once in the city, I found the building where the other interpreters were quartered, and was told by my friends that there was an empty bed. They described the destruction they had seen in various Japanese cities, but they had not yet realized the terrible significance of the atomic bomb.

They all agreed that it would take at least 50 years for Japan to recover its pre-war status. Nobody spoke of a possible revival of Japan. This may be why only 20 or 30 of the thousand or so young men trained in Japanese by the Navy and Army attempted to find a career which involved knowledge of the language.

My second visit to Japan was in 1953, this time in Kyoto as a graduate student. I chose Kyoto not only because of its history, but because it had escaped bombing. My wartime friend, Otis Cary, then teaching at Doshisha University, found an ideal place for me to live. I intended to study at Kyoto University, but in fact, I did not spend much time there because the professor so seldom appeared. As it grew colder in the unheated classroom, I felt less and less ready to wait in vain for the professor, and was glad to spend my time in Kyoto sightseeing instead of shivering in a classroom.

Two "maiko," or apprentice geisha, pay a round of visits to their teachers of traditional Japanese arts and teahouse owners during the annual summer "hassaku" event in Kyoto's Gion district on Aug.1. | COURTESY OF DONALD KEENE

I enjoyed wandering at random in the city, fascinated by the names of places I knew from works of Japanese literature and history. The streets were surprisingly quiet, probably because at the time there were no privately owned cars in Kyoto, only company vehicles. I was delighted one day when I saw two elderly ladies happening to meet while crossing in the middle of Kawaramachi, the busiest street in the city. They politely removed their haori jackets and bowed to each other, not in the least worried by possible traffic. Of course, not everything in Kyoto was so pleasing. I saw slum areas not only around the railway station but in the middle of the city, and there were many boys eager to polish one’s shoes. But I managed to accept these sad results of the long warfare that the Japanese had suffered.