What it means to live in a machiya

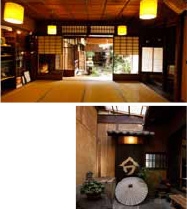

ono tei

The Ono Residence is a typical machiya representative of the omoteya-zukuri style. Its storehouse (built in 1903) and principal residential quarters incorporates the Sukiyabashi design. The playful sprit of the carpenters can be seen everywhere, including a unique design that takes advantage of a curve across the storage bins just below the ceiling. In January 2012 the Ono Residence was selected by the City of Kyoto as one of the “buildings and gardens worthy of preservation in recognition of its contribution to the city landscape.”

Haruhisa Ono

Mr. Ono is willing to share his machiya with overnight guests (one group per day). For details, call 075-531-2601.

My machiya is like a prodigal daughter. She splurges a lot, but I love her dearly.

“I bought this machiya simply because it looked great, but the truth is I didn’t know anything about it,” Haruhira Ono confides. He had to enlist the help of a master carpenter and a college professor who lectures on machiya. Armed with the knowledge gained through these lectures, Ono was finally able to establish a “dialogue” with his machiya, which he loves dearly. “But I warn you, she is a real money eater.” For his machiya, which had been vacant for 10 years prior to his purchase, he had to spend five million yen just to harden the foundation.

The beauty of a machiya lies in its spiritual charm, according to Ono. “I feel totally relaxed in here. When you sit down on the tatami mat, the space between your head and the ceiling is just the right distance ‒ very comfortable. And a machiya is very quiet. In summer, the wind blows in from the gardens and lowers the room temperatures. The difference between indoors and outdoors may be as large as five degrees Celsius.” In winter, however, the house gets very chilly. Ono’s toes were covered with frostbite during the first winter. “To cope with the winter chill, I realigned my thinking a little. I just bundle up even while I am home. This way, I’ve had no problem surviving the freezing winter with just one kerosene heater since my second year living here,” Ono says. “Thanks to my machiya, my body and soul are completely attuned to the four distinctive seasons and their passage.” His machiya has become his beloved nesting ground.

Furukawa tei

Built in the early Showa era, Furukawa’s machiya is relatively new. Compared with its elder cousins, its ceilings are high, and some rooms are western style. Nonetheless, it is built in the classical omoteya-zukuri architectural style, which typically combines the residential and working spaces. “I was pleasantly surprised at how comfortable it was to live in a machiya,” notes Furukawa. “I anticipated more inconveniences.”

Rieko Furukawa

Imahara Machiya Furukawatei’s rear reception room overlooking the garden is available for nabe pot parties. Lunch is also served, on Fridays only. For a reservation, call 075-203-5169.

Machiya are the manifestation of a lifestyle

“This machiya was built by my maternal great grandfather in 1929,” Furukawa explains as she ushers me into a sun-drenched reception room facing a garden. The house is notable for its abundant use of glass, a fixture that began to enter the life of people only in the Showa era; hence the rooms are unusually well-lit, unlike most machiya houses. It features luxury materials like Yakusugi cedar for the second-floor ceiling.

“My great grandfather was a kumihimo (cordbraiding) craftsman, and he was not particularly wealthy. But according to his daughter, who is my grandma, he was ‘scrupulously diligent’ and didn’t fool around or splurge on drinking or hobbies, and poured all the money he earned into this machiya.”

His family understood his deep affection for the house and have done very little to alter it. As a result, this machiya’s original shape and glory is well preserved.

Only after Furukawa moved into this machiya six years ago did she understand the wisdom of the people involved in the construction of this house, which was very much centered on how to let its inhabitants lead a pleasant life. “This house is the manifestation of a pleasant lifestyle. And I have come to appreciate it.”

What Furukawa discovered were the unspoken insights into life that her ancestors left many years ago.

Hirohisa Tomiie

Registered Class-1 Architect, Tomiie Architectural Design Firm

Carpenters’ expertise and connections are key to the successful revitalization of machiya houses.

Hirohisa Tomiie is an architect who advocates the restoration of machiya houses. Machiya provide agility and mobility to their inhabitants. Houses do get older, but replacing the malfunctioning parts is all it takes to prolong the life of a machiya. For this, the expertise of carpenters is absolutely essential, says Tomiie.heritage and no longer remove the lattices, there is one less reason to preserve the full functionality that the machiya offer. As a result, some residents decide to demolish those doors to make room for a garage space. I have been involved in machiya house restoration projects for two years, attempting to bring back their traditional character and shape.” “Restoration may entail repairing warped frames, refilling earthen walls and replacing old beams with new ones for added strength. We try to stay true to the original floor layouts. We sometimes finish the bare “Machiya are like boxes containing a lifestyle, and they wouldn’t have existed had it not been for the lifestyle in need of that box, and as the lifestyle that requires machiya is disappearing, so are the reasons to live in one” Tomiie explains. “For instance, the degoshi wooden lattices that cover a machiya’s doors are removable. During the Jizo-Bon festival, the lattices are removed so that the street and front chamber are spatially connected, and children are allowed to enter and exit the house as they please. As a growing number of residents decide not to observe this cultural floor of the doma space with a floor covering or install modern kitchen components. If indoor lighting is not adequate, we create a skylight out of the atrium ceiling and we refit mushiko windows (windows covered with slits cut into plaster walls) on upper floors with aluminum panes.

Some earthen walls were covered up with veneer boards in the past and as a result the walls have deteriorated. To rescue the original walls, we strip off the veneer to allow the walls to breathe in fresh air.

We buy and clean second-hand fixtures that were part of demolished machiya to refit the one being renovated, since some fixtures, like hand-blown glass plates, are no longer produced. Restoring a machiya requires the ability to coordinate all aspects of the work involved, and being able to build a house is not enough. I am learning a lot from the carpenters. They are not only fully versed with traditional building techniques, they know where to go to find the right material for refitting. Their connections are indispensable.”