The war is not over until Russia changes

For some states, the Second World War ended in 1945; for others, the spectrum of totalitarianism continued until 1991 with the fall of the Berlin Wall, the reunification of Germany, the withdrawal of Soviet troops, and independence. But this was not a complete or linear process. On the one hand, the world is still divided among victors and vanquished and Russia’s, as acknowledged by some, nominally democratic regime continues its predecessors’ policy of colonization that seeks to advance its imperial influence, including its territorial control over the resource-rich and geopolitically significant Japanese Northern Territories. In this scheme, Russia is less of a “guarantor” of the post-WWII peace and more its “beneficiary,” treating territory as the fair spoils of a victor.

Among the spoils are Japan’s Northern Territories. Russia’s sole claim to the island complex is that of a conqueror and a colonizer. The occupation and ethnic cleansing of the island complex was the wrong foundation upon which to built a solid post-WWII order. The right to return for the people of these islands permeates every democratic principle to which, theoretically at least, Russia adheres to. It is now high time to right this wrong. But convincing Russia to respect the notion of a principled world order is not a challenge for the faint at heart.

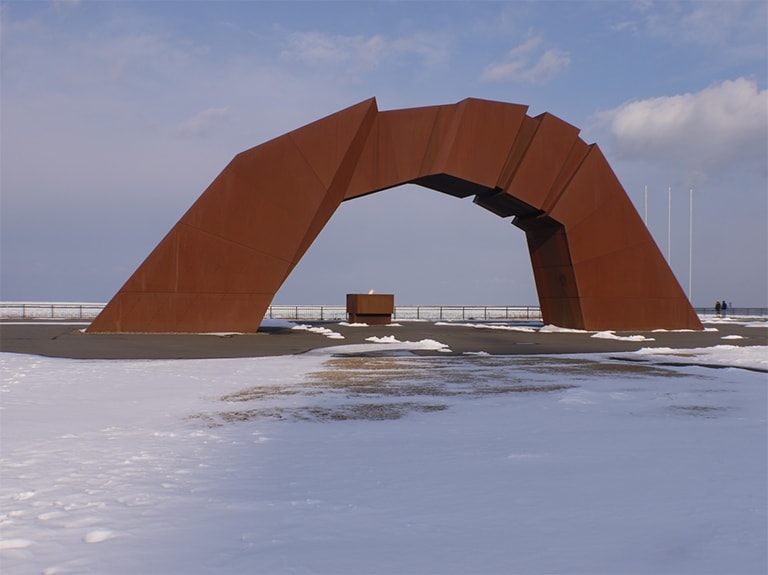

The Four Islands Bridge Memorial, near Nemuro in Hokkaido, was built to express Japan’s hope for the return of it’s northern territories

From the early 1990s and until the late 2000s, the EU sought to actively de-securitize its relationship with Russia. In a world where the terms independence, democratization and Europeanization were used interchangeably, the assumption was that the post-Soviet space would be subsumed into a politically and normatively aligned template, in which Russia itself would have associated membership. The idea was that Europe would become an ecosystem of post-nation-state polities that share common norms, regulations, markets, and constitutional values. From a Georgian perspective, this was a narrative that affirmed our right to exist as a people of distinct cultural, historical and religious identity, but also to reframe our relationship with Russia from “post-colonial” to shared membership of a European Commonwealth.